Business Lessons from a Broken Hip

From a hospital bed, one gets a unique vantage point on systems. And the truth I've seen? 'Efficiency' is often just a polite word for transferring friction from your spreadsheet directly onto your customer.

Cristian Brownlee

Author

It would appear my hip decided, rather spectacularly, to part ways with the rest of my skeletal agenda. I write this from a hospital bed, a position which, while not ideal for one's posture, is absolutely eye-opening for one's perspective.

My new surroundings are a marvel. Truly. A marvel of process.

Within hours, I have been 'admitted', 'triaged', 'processed', 'scanned', and 'allocated'. The entire operation is a vast, complex dance of 'logical' workflow. It's the kind of thing a management consultant dreams about.

There is just one small problem.

In the last 24 hours, I have explained the rather tedious story of my fall, given my full name, my date of birth, and a comprehensive breakdown of my existing medical conditions to no fewer than eighteen different people. The admissions clerk. The triage nurse. The ward nurse. The radiographer. The porter. The consultant. The anaesthetist.

Each interaction is, in isolation, perfectly 'efficient'. Every person is following their checklist. The problem is, they are following their checklist, not mine.

The Efficient System vs. The Human User

This, right here, is the grand illusion of the modern age. We have confused 'efficiency' with 'logic'.

The hospital, like so many of our businesses, is not designed for the patient. It is designed for the spreadsheet. The workflow is optimised to make the system's life easier, to ensure every box is ticked and every data point is captured.

The "inefficiency": the frustration, the repetition, the bewilderment: is not eliminated. Good heavens, no. It is simply transferred from the system directly onto the human user.

From this horizontal perch, my capacity for spotting friction has become exquisitely sharp. I can see the absurdity with perfect clarity. This is the grand folly of designing for a statistical ghost. The system processes 'the average patient' with flawless precision, but it utterly fails the actual, individual, flesh-and-blood human lying in the bed.

This is not a complaint about the NHS. It is an observation about business.

We do this. Every day.

We do it with our automated phone trees. "Please listen carefully as our options have changed..." This is a signal that the company is optimising its own call-routing at the direct expense of the customer's time and sanity.

We do it when we force a customer to tell their story to a chatbot, then to a "Level 1" support agent, and then, infuriatingly, all over again to a "Level 2" manager. The system's 'efficiency' in logging tickets is pure, unadulterated friction for the customer.

Friction is a Cost You Can't See

The "logical" mind looks at this and sees a cost-saving. The human-centric mind sees a catastrophic, value-destroying signal.

When your system makes me, the customer, do the repetitive work, you are sending a very clear message: "My time is valuable. Yours is not."

You are communicating that your internal process is more important than my external experience. It's the business equivalent of inviting someone to dinner and asking them to wash the dishes before the first course. It's just bad manners. And it is terrible business.

A truly counter-intuitive business, a brave business, would ask a different question.

Instead of: "How do we make this process more efficient for us?"

Ask: "How can we take the friction out of the system, even if it costs us a little more?" How do we make the experience of interacting with us one of effortless, human delight?

The real innovation is not in building a flawless spreadsheet. It is in building a system so humane, so intuitive, and so thoughtful that the customer never even feels the process at all.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I believe I see number nineteen approaching. I must go and tell him my date of birth.

Related Articles

The Equality Act: A Toothless Tiger

The Equality Act is designed to protect us. But without active enforcement, it is merely a suggestion. Why are we forcing the individuals it claims to protect to fund their own justice against the deepest pockets?

The Battlefield for Attention: Why Your Strategy is Losing to 'Brainrot'

We believe our strategies fail because they are wrong. The truth is often simpler: they fail because nobody is actually listening.

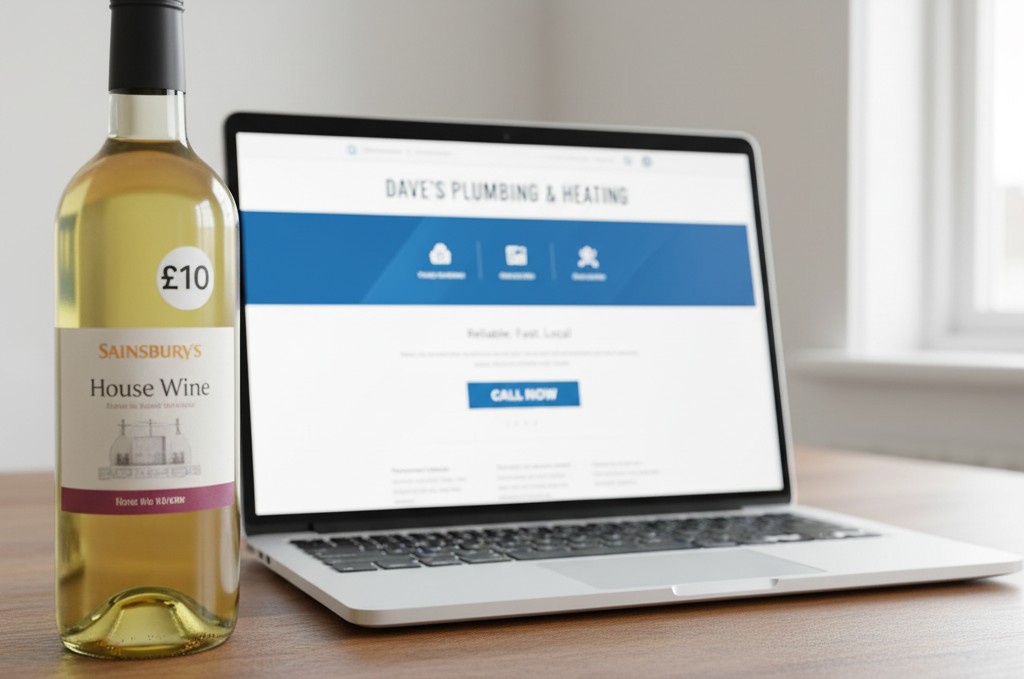

The Sainsbury's Wine Delusion: Your 'Simple Fix' is Someone Else's Miracle

I gave my plumber a 'simple' website instead of a cheap bottle of wine. His reaction taught me a profound lesson about value, expertise, and the ingenuity we take for granted.